In light of the recent re-appraisal of Hilma af Klint's Spiritualist paintings in the history of Abstract Art, this exhibition explores the prevalence of spirituality in post-war abstraction.

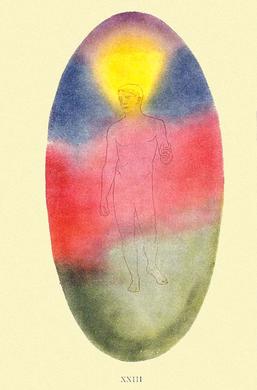

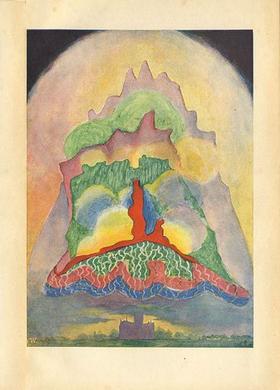

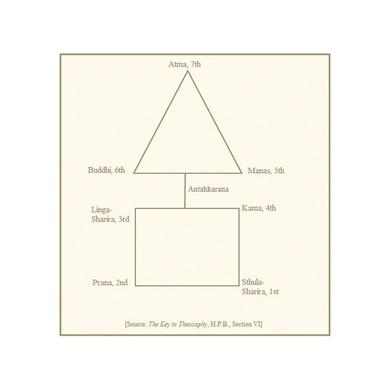

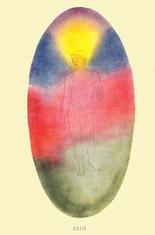

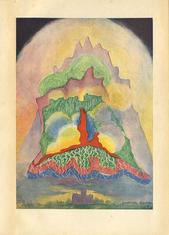

The influence of "occult" Theosophy and esoteric thought upon pioneers of abstract art in the early twentieth century such as Kandinsky, Kupka, Malevich and Mondrian has been almost erased from modern art history. But it is evident that Theosophist writings such as Annie Besant & Charles Leadbeater's "Thought Forms" (1901), and "Man Visible & Invisible" (1902), along with the teachings of their protégé Rudolf Steiner, were fundamental to these artists' motivations, in giving expression to the spiritual dimension and manifesting the "universal mystery" through "art".

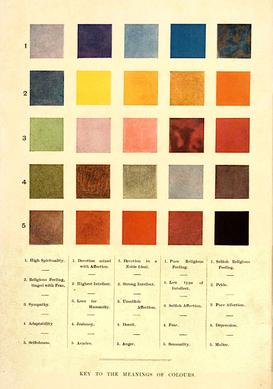

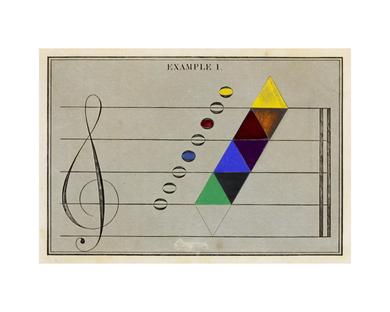

This exhibition looks at how spirituality continued to be an important source of inspiration for artists in the post-war years, not least Claude Bellegarde whose abstract "Chromagraph" paintings derived from spiritual resonances, linked to Besant & Leadbeater's Theosophist ideas and vibrant diagrams of aural energies along with their "Key to the meaning of colours" which defined the spiritual symbolism of the spectrum. Bellegarde became a devotee of Krishnamurti, (whose guru status had been created by Leadbeater's messianic proclamations on "discovering" him as a child.)

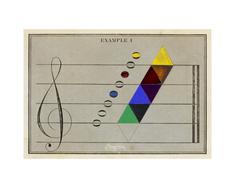

In a similar vein, Serge Charchoune was influenced by Krishnamurti's counterpart, Rudolph Steiner, whose "Anthroposophical" theories inspired Charchoune's undulating abstract paintings created from the concept of music resonating the soul. A theme which Kandinsky had also discussed in his 1910 essay "On the Spiritual in Art".

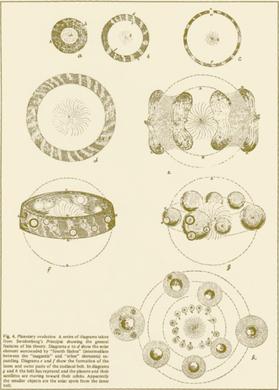

Marie Raymond (and her son Yves Klein) was a follower of Max Heindel's Rosicrucianism as laid out in his 1909 treatise "The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception" based on the 15th century legends of Christian Rosenkreuz, which called for a reformation of mankind and re-connection with the spiritual realm. Raymond's vibrant gestural abstract compositions seek to help the viewer to transcend the material world.

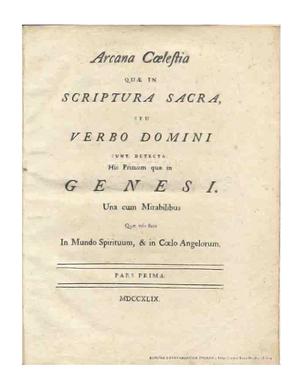

Meanwhile the Russian émigré Cubist turned metaphysical surrealist, Léopold Survage, became captivated by the 18th century Swedish scientist turned visionary cosmologist, Emanuel Swedenborg, who believed he was a conduit for spirits and angels, was courted by the King and Queen of Sweden, and published his "heavenly doctrine" on reforming religion in “Arcana Coelestia” in 1749. Survage's compositions were increasingly populated with symbolism from Swedenborg's writings.

Drawing more on Eastern beliefs was Alfred Reth who rejected his early rational Cubism for arching forms of colour interspersed with sand, and other earthly materials, in accordance with ideas of geometry such as those laid out in the Manasara scriptures.

The Swiss "Abstraction Creation" painter Leo Leuppi, also sought the "absolute truth" through geometric abstraction, akin to the Neo-Plastiscm of Mondrian and Van Doesburg abiding by the Hegelian notion that by reducing art to its purist form the Spiritual realm will be revealed.

Besides these more overt spiritual influences, throughout post-war abstraction artists are often found using phrases such as “the absolute”, “universal mystery”, or “the inner self”. It is undeniably a rich vein that runs through modern art, perhaps reflecting Susan Sontag’s notion of “the mind’s need or capacity for self-estrangement”.

Other artists in the exhibition include Georges Collignon, Emile Gilioli, Marcel Pouget, and Léon Zack.

A longer essay and reading list can be downloaded via the 'Press Release' link below: